The Analyst · Az analizáló

I. Though I am a Stranger to your Person, yet I am not, Sir, a Stranger to the Reputation you have acquired, in that branch of Learning which hath been your peculiar Study; nor to the Authority that you therefore assume in things foreign to your Profession, nor to the Abuse that you, and too many more of the like Character, are known to make of such undue Authority, to the misleading of unwary Persons in matters of the highest Concernment, and whereof your mathematical Knowledge can by no means qualify you to be a competent Judge. Equity indeed and good Sense would incline one to disregard the Judgment of Men, in Points which they have not considered or examined. But several who make the loudest Claim to those Qualities, do, nevertheless, the very thing they would seem to despise, clothing themselves in the Livery of other Mens Opinions, and putting on a general deference for the Judgment of you, Gentlemen, who are presumed to be of all Men the greatest Masters of Reason, to be most conversant about distinct Ideas, and never to take things on trust, but always clearly to see your way, as Men whose constant Employment is the deducing Truth by the justest inference from the most evident Principles. With this bias on their Minds, they submit to your Decisions where you have no right to decide. And that this is one short way of making Infidels I am credibly informed.

1. Jóllehet személye ismeretlen számomra, uram, de nem ismeretlen a hírnév, amelyet az Ön által művelt tudományágban szerzett; sem pedig az, hogy ezen a réven milyen tekintélyre tett szert a foglalkozásán kívül eső dolgokat illetően, aminthogy az sem, hogy Ön és a túlságosan is sok hasonszőrű hogyan él vissza e meg nem szolgált tekintéllyel, hogyan vezeti félre az óvatlanokat a legnagyobb körültekintést igénylő dolgokban, melyeknek mérvadó elbírálására matematikai ismereteik semmiképpen sem jogosítják fel Önöket. A méltányosság és a jóérzés arra ösztönözne, hogy figyelmen kívül hagyjuk az olyan emberek véleményét, akik nem vizsgálták meg kellőképpen azt, amiről ítéletet formálnak. Sokan azonban, akik fennen hirdetik, mennyire körültekintőek a véleményalkotásban, éppen azt teszik, amit olyannyira megvetni látszanak: mások nézeteinek libériájába bújnak, és általános hódolattal fogadják az Önök véleményét, uraim, akikről azt tartják, hogy minden ember közül a legnagyobb mesterei az észnek, legalaposabb ismerői a világos ideáknak, és soha semmit vakon el nem hisznek, hanem mindent pontosan átgondolnak, olyan férfiak módjára, akiknek állandó foglalatosságuk, hogy a legnyilvánvalóbb alapelvekből a leghelyesebb következtetések révén az igazsághoz jussának. Ezzel az előítélettel az elméjükben, alávetik magukat az Önök döntéseinek ott, ahol Önöknek nincs joguk dönteni. S így, mint megbízható forrásból értesültem róla, rövid úton hitetlenekké válnak.

II. Whereas then it is supposed, that you apprehend more distinctly, consider more closely, infer more justly, conclude more accurately than other Men, and that you are therefore less religious because more judicious, I shall claim the privilege of a Free-Thinker; and take the Liberty to inquire into the Object, Principles, and Method of Demonstration admitted by the Mathematicians of the present Age, with the same freedom that you presume to treat the Principles and Mysteries of Religion; to the end, that all Men may see what right you have to lead, or what Encouragement others have to follow you. It hath been an old remark that Geometry is an excellent Logic. And it must be owned, that when the Definitions are clear; when the Postulata cannot be refused, nor the Axioms denied; when from the distinct Contemplation and Comparison of Figures, their Properties are derived, by a perpetual well-connected chain of Consequences, the Objects being still kept in view, and the attention ever fixed upon them; there is acquired a habit of reasoning, close and exact and methodical: which habit strengthens and sharpens the Mind, and being transferred to other Subjects, is of general use in the inquiry after Truth. But how far this is the case of our Geometrical Analysts, it may be worth while to consider.

2. Mivel pedig Önökről az járja, hogy felfogásuk tisztább, megfontolásaik érettebbek, következtetéseik helyesebbek, eredményeik pedig pontosabbak, mint másokéi, továbbá, hogy jobb az ítélőképességük, s ezért kevésbé vallásosak, én is igényt tartok a szabadgondolkodók előjogára, és veszem a bátorságot, hogy ugyanolyan szabadon vizsgáljam meg a korunk matematikusai által elfogadott tárgyakat, alapelveket és bizonyítási módszereket, mint ahogyan állítólag Önök teszik, uraim, a vallás alapelveivel és misztériumaival. Mindezt azzal a céllal teszem, hogy mindenki láthassa, milyen joguk van Önöknek a vezetésre, és mi bátoríthat valakit arra, hogy kövesse Önöket. Régi igazság, hogy a geometria logikája kiváló. Valóban, de csak ha a definíciók világosak, ha a posztulátumok cáfolhatatlanok és az axiómák tagadhatatlanok; ha az alakzatok gondos megszemléléséből és összehasonlításából a következmények megszakítás nélkül összekapcsolódó láncolatán át vezetjük le tulajdonságaikat, miközben a tárgyat mindvégig szem előtt tartjuk, s figyelmünk egy pillanatra sem lankad; ezzel olyan gondolkodásmódra teszünk szert, amely fegyelmezett, pontos és módszeres, élesíti és erősíti az elmét, más tárgyakra alkalmazva pedig általánosan használható az igazság keresésekor. Hogy azonban mennyire nem ez a helyzet a mi geometriai analizálóink esetében, azt érdemes közelebbről szemügyre venni.

III. The Method of Fluxions is the general Key, by help whereof the modern Mathematicians unlock the secrets of Geometry, and consequently of Nature. And as it is that which hath enabled them so remarkably to outgo the Ancients in discovering Theorems and solving Problems, the exercise and application thereof is become the main, if not sole, employment of all those who in this Age pass for profound Geometers. But whether this Method be clear or obscure, consistent or repugnant, demonstrative or precarious, as I shall inquire with the utmost impartiality, so I submit my inquiry to your own Judgment, and that of every candid Reader. Lines are supposed to be generated(1) by the motion of Points, Planes by the motion of Lines, and Solids by the motion of Planes. And whereas Quantities generated in equal times are greater or lesser, according to the greater or lesser Velocity, wherewith they increase and are generated, a Method hath been found to determine Quantities from the Velocities of their generating Motions. And such Velocities are called Fluxions: and the Quantities generated are called flowing Quantities. These Fluxions are said to be nearly as the Increments of the flowing Quantities, generated in the least equal Particles of time; and to be accurately in the first Proportion of the nascent, or in the last of the evanescent, Increments. Sometimes, instead of Velocities, the momentaneous Increments or Decrements of undetermined flowing Quantities are considered, under the Appellation of Moments.

3. A fluxiók módszere az az általános kulcs, amelynek segítségével a modern matematikusaink felnyitják a geometria és ezzel a természet titkait. És minthogy ez tette képessé őket arra, hogy oly figyelemreméltóan felülmúlják a régieket a problémák megoldásában és a tantételek felállításában, e módszer gyakorlása és alkalmazása vált a fő, ha ugyan nem az egyedüli foglalatosságává azoknak, akik manapság mély gondolkodású geométernek számítanak. Hogy azonban e módszer tiszta-e vagy zavaros, ellentmondásmentes vagy önellentmondó, meggyőző vagy kétes, azt a legteljesebb pártatlansággal meg fogom vizsgálni, és eredményeimet az Önök és minden tárgyilagos olvasó ítéletére bocsátom. Feltevésük szerint a vonalak a pontok mozgásából, a síkok a vonalak mozgásából,1 a testek pedig a síkok mozgásából jönnek létre. És mivel az azonos idők alatt létrejövő mennyiségek növekedésük és létrejöttük gyorsasága szerint kisebbek vagy nagyobbak, kidolgoztak egy módszert a mennyiségeknek az őket létrehozó mozgások sebessége alapján való meghatározására. Ezeket a sebességeket nevezik fluxióknak, a létrehozott mennyiségeket pedig fluens mennyiségeknek. A fluxiókról azt állítják, hogy csaknem azonosak a fluens mennyiségeknek a legkisebb egyenlő időtartamok alatt létrejövő növekményeivel; pontosabban, a születőben levő növekmények közül az elsők, az eltűnőben levők közül pedig az utolsók arányával. Néha a sebességek helyett a meghatározatlan fluens mennyiségek pillanatnyi növekményeit (inkrementum) vagy dekrementumait vizsgálják, s ezeket momentumoknak nevezik.

IV. By Moments we are not to understand finite Particles. These are said not to be Moments, but Quantities generated from Moments, which last are only the nascent Principles of finite Quantities. It is said, that the minutest Errors are not to be neglected in Mathematics: that the Fluxions are Celerities, not proportional to the finite Increments though ever so small; but only to the Moments or nascent Increments, whereof the Proportion alone, and not the Magnitude, is considered. And of the aforesaid Fluxions there be other Fluxions, which Fluxions of Fluxions are called second Fluxions. And the Fluxions of these second Fluxions are called third Fluxions: and so on, fourth, fifth, sixth, $\textit &c.$ ad infinitum. Now as our Sense is strained and puzzled with the perception of Objects extremely minute, even so the Imagination, which Faculty derives from Sense, is very much strained and puzzled to frame clear Ideas of the least Particles of time, or the least Increments generated therein: and much more so to comprehend the Moments, or those Increments of the flowing Quantities in statu nascenti, in their very first origin or beginning to exist, before they become finite Particles. And it seems still more difficult, to conceive the abstracted Velocities of such nascent imperfect Entities. But the Velocities of the Velocities, the second, third, fourth, and fifth Velocities, $\textit &c.$ exceed, if I mistake not, all Humane Understanding. The further the Mind analyseth and pursueth these fugitive Ideas, the more it is lost and bewildered; the Objects, at first fleeting and minute, soon vanishing out of sight. Certainly in any Sense a second or third Fluxion seems an obscure Mystery. The incipient Celerity of an incipient Celerity, the nascent Augment of a nascent Augment, i.e. of a thing which hath no Magnitude: Take it in which light you please, the clear Conception of it will, if I mistake not, be found impossible, whether it be so or no I appeal to the trial of every thinking Reader. And if a second Fluxion be inconceivable, what are we to think of third, fourth, fifth Fluxions, and so onward without end?

4. A momentumokon nem kicsiny véges részecskéket kell értenünk. Ezeket ugyanis nem momentumoknak nevezik, hanem momentumokból létrejövő mennyiségeknek, a momentumok viszont csupán a véges mennyiségek születőben levő kezdeményei. Azt tartják, hogy a matematikában a legparányibb hibák sem elhanyagolhatók, hogy a fluxiók sebességek, amelyek nem a véges növekményekkel arányosak, legyenek bár ezek mégoly kicsinyek, hanem csak a momentumokkal, vagyis a születőben levő növekményekkel, amelyeknek a nagyságát nem, csak az arányát veszik tekintetbe. A mondott fluxióknak szintén vannak fluxióik, amelyeket másodrendű fluxióknak neveznek. A másodrendű fluxiók fluxióit pedig harmadrendű fluxióknak és így tovább, vannak negyed-, ötöd-, hatodrendű stb. fluxiók, ad infinitum. Mármost, amint a rendkívül kicsiny objektumok érzékelése megerőlteti és összezavarja érzékeinket, úgy igencsak megerőltető és zavarba ejtő képzeletünk számára – ez a képességünk az érzékelésből ered –, hogy világos ideákat formáljon az idő legkisebb részecskéiről vagy az ezekben létrejövő legkisebb növekményekről; s még inkább, hogy felfogja a momentumokat, azaz a fluens mennyiségek növekményeit in statu nascenti, tehát létrejöttük legkezdetén, mielőtt még véges mennyiségekké válnának. Ennél is nehezebbnek látszik felfogni az ilyen születőben levő, befejezetlen entitások elvont sebességeit. A sebességek sebességei, a másod-, harmad-, negyed- és ötödrendű sebességek stb. azonban, ha nem tévedek, teljességgel meghaladják az emberi felfogóképességet. Minél mélyebben elemzi és minél messzebbre követi az elme e megfoghatatlan ideákat, annál zavartabbá és tanácstalanabbá válik; a kezdetben is parányi, eltűnőben levő objektumok hamarosan szertefoszlanak. Egy másod- vagy harmadrendű fluxió minden értelemben homályos misztériumnak tűnik. Egy kezdődő sebesség kezdődő sebessége, egy születőben levő növekmény születőben levő növekménye, azaz egy nagyság nélküli mennyiség – nos, ennek világos felfogása, akárhogyan vesszük is, úgy vélem, lehetetlen; hogy így van-e vagy sem, azt gondolkodó olvasóim ítéletére bízom. Ha pedig már egy másodrendű fluxió felfoghatatlan, mit gondoljunk a harmad-, negyed-, ötödrendű fluxiókról, és így tovább a végtelenségig?

V. The foreign Mathematicians are supposed by some, even of our own, to proceed in a manner, less accurate perhaps and geometrical, yet more intelligible. Instead of flowing Quantities and their Fluxions, they consider the variable finite Quantities, as increasing or diminishing by the continual Addition or Subduction of infinitely small Quantities. Instead of the Velocities wherewith Increments are generated, they consider the Increments or Decrements themselves, which they call Differences, and which are supposed to be infinitely small. The Difference of a Line is an infinitely little Line; of a Plane an infinitely little Plane. They suppose finite Quantities to consist of Parts infinitely little, and Curves to be Polygons, whereof the Sides are infinitely little, which by the Angles they make one with another determine the Curvity of the Line. Now to conceive a Quantity infinitely small, that is, infinitely less than any sensible or imaginable Quantity, or any the least finite Magnitude, is, I confess, above my Capacity. But to conceive a Part of such infinitely small Quantity, that shall be still infinitely less than it, and consequently though multiply’d infinitely shall never equal the minutest finite Quantity, is, I suspect, an infinite Difficulty to any Man whatsoever; and will be allowed such by those who candidly say what they think; provided they really think and reflect, and do not take things upon trust.

5. A külföldi matematikusokról2 sokan feltételezik, még némelyik honfitársunk is, hogy geometriailag talán kevésbé szigorú, mégis érthetőbb módszert alkalmaznak. A fluens mennyiségek és ezek fluxiói helyett ők változó véges mennyiségekről beszélnek, s ezeket úgy tekintik, mint amelyek végtelenül kicsiny mennyiségek folytonos felvételével vagy elvesztésével növekednek, illetve csökkennek. A növekmények létrejöttének sebességei helyett magukat a növekményeket vagy dekrementumokat vizsgálják, ezeket differenciáknak nevezik, és végtelenül kicsinyeknek tartják. Egy szakasz differenciája egy végtelenül kicsiny szakasz, egy síké pedig egy végtelenül kicsiny sík. A véges mennyiségekről felteszik, hogy végtelenül kicsiny részekből állnak, a görbék pedig olyan sokszögek, amelyeknek oldalai végtelenül kicsik, s az általuk bezárt szögek, meghatározzák a vonal görbületét. Nos, egy végtelenül kicsiny, azaz minden érzékelhető vagy elképzelhető, illetve a legkisebb véges mennyiségnél is végtelenül kisebb mennyiség felfogása – bevallom – meghaladja képességeimet. És fogalmat alkotni egy ilyen végtelenül kis mennyiség végtelenül kis részéről, amely végtelenszer megsokszorozva sem lesz akkora, mint akár a legkisebb véges mennyiség – ez, gyanítom, végtelenül nehéz mindenki számára; amit el is ismerne mindenki, aki őszintén kimondja, amit gondol, feltéve persze, hogy valóban gondolkodik, s nem csak elhiszi, amit mondanak neki.

VI. And yet in the calculus differentialis, which Method serves to all the same Intents and Ends with that of Fluxions, our modern Analysts are not content to consider only the Differences of finite Quantities: they also consider the Differences of those Differences, and the Differences of the Differences of the first Differences. And so on ad infinitum. That is, they consider Quantities infinitely less than the least discernible Quantity; and others infinitely less than those infinitely small ones; and still others infinitely less than the preceding Infinitesimals, and so on without end or limit. Insomuch that we are to admit an infinite succession of Infinitesimals, each infinitely less than the foregoing, and infinitely greater than the following. As there are first, second, third, fourth, fifth $\textit &c.$ Fluxions, so there are Differences, first, second, third fourth, $\textit &c.$ in an infinite Progression towards nothing, which you still approach and never arrive at. And (which is most strange) although you should take a Million of Millions of these Infinitesimals, each whereof is supposed infinitely greater than some other real Magnitude, and add them to the least given Quantity, it shall be never the bigger. For this is one of the modest postulata of our modern Mathematicians, and is a Corner-stone or Ground-work of their Speculations.

6. Ráadásul a calculus differentialisban, amely ugyanazokra a célokra szolgál, mint a fluxiók módszere, modern analitikusaink nem érik be azzal, hogy csupán véges mennyiségek differenciáiról beszéljenek, hanem e differenciák differenciáinak fogalmát is bevezetik, sőt a differenciák differenciáinak differenciáiét is, és így tovább ad infinitum. Azaz olyan mennyiségeket gondolnak el, amelyek végtelenül kisebbek, mint a legkisebb megkülönböztethető mennyiség; sőt a végtelenül kicsinyeknél végtelenül kisebbeket is, azután újra kisebbeket, mint a megelőzőek, minden határ nélkül a végtelenségig. Ily módon az infinitezimális mennyiségek végtelen sorozata áll elő, amelyben minden tag végtelenül kisebb, mint a megelőző, és végtelenül nagyobb, mint a rákövetkező. És ahogy vannak első-, másod-, harmad-, negyed-, ötödrendű stb. fluxiók, úgy vannak első-, másod-, harmad-, negyedrendű stb. differenciák, végtelen sorban tartva a semmihez, amelyhez folytonosan közelítenek, de soha el nem érkeznek. Ami pedig még furcsább, ha milliószor milliónyit veszünk ezekből az infinitezimálisokból, amelyek mindegyike végtelenül nagyobb, mint valamely más reális nagyság, és hozzáadjuk akár a legkisebb adott mennyiséghez, az utóbbi semmivel sem lesz nagyobbá. Ez ugyanis egyike modern matematikusaink szerény posztulátumainak, és spekulációiknak sarkpontja és talpköve.

VII. All these Points, I say, are supposed and believed by certain rigorous Exactors of Evidence in Religion, Men who pretend to believe no further than they can see. That Men, who have been conversant only about clear Points, should with difficulty admit obscure ones might not seem altogether unaccountable. But he who can digest a second or third Fluxion, a second or third Difference, need not, methinks, be squeamish about any Point in Divinity. There is a natural Presumption that Mens Faculties are made alike. It is on this Supposition that they attempt to argue and convince one another. What, therefore, shall appear evidently impossible and repugnant to one, may be presumed the same to another. But with what appearance of Reason shall any Man presume to say, that Mysteries may not be Objects of Faith, at the same time that he himself admits such obscure Mysteries to be the Object of Science?

7. Mindezt pedig, mint mondom, azok tételezik fel és hiszik el, akik a vallási dolgokban szigorú bizonyítékokat követelnek, akik csak a saját szemüknek hisznek. Mert az még csak érthető, hogy olyan emberek, akik világos gondolatmenetekhez szoktak, nehezen fogadják el a homályosakat; ám azok, akik képesek megemészteni egy másod- vagy harmadrendű fluxiót, egy másod- vagy harmadrendű differenciát, úgy gondolom, ne legyenek finnyásak a kinyilatkoztatás egyetlen tételét illetően sem. Közkeletű feltevés, hogy az emberek képességei egyformák, E feltevés alapján próbálunk érvelni és meggyőzni egymást. Ami tehát nyilvánvalóan lehetetlennek és visszatetszőnek tűnik az egyik ember szemében, azt feltehetően a másik is annak találja majd. De vajon miféle ésszerűség látszatával állíthatja valaki, hogy misztériumok nem lehetnek a hit tárgyai, miközben ő maga elfogadja, hogy efféle homályos misztériumok a tudomány tárgyai legyenek?

VIII. It must indeed be acknowledged, the modern Mathematicians do not consider these Points as Mysteries, but as clearly conceived and mastered by their comprehensive Minds. They scruple not to say, that by the help of these new Analytics they can penetrate into Infinity it self: That they can even extend their Views beyond Infinity: that their Art comprehends not only Infinite, but Infinite of Infinite (as they express it) or an Infinity of Infinites. But, notwithstanding all these Assertions and Pretensions, it may be justly questioned whether, as other Men in other Inquiries are often deceived by Words or Terms, so they likewise are not wonderfully deceived and deluded by their own peculiar Signs, Symbols, or Species. Nothing is easier than to devise Expressions or Notations for Fluxions and Infinitesimals of the first, second, third, fourth, and subsequent Orders, proceeding in the same regular form without end or limit $\dot{x}$. $\ddot{x}$. $\dddot{x}$. $\ddddot{x}$. $\textit &c.$ or $dx$. $ddx$. $dddx$. $ddddx$. $\textit &c.$ These Expressions indeed are clear and distinct, and the Mind finds no difficulty in conceiving them to be continued beyond any assignable Bounds. But if we remove the Veil and look underneath, if laying aside the Expressions we set ourselves attentively to consider the things themselves, which are supposed to be expressed or marked thereby, we shall discover much Emptiness, Darkness, and Confusion; nay, if I mistake not, direct Impossibilities and Contradictions. Whether this be the case or no, every thinking Reader is intreated to examine and judge for himself.

8. Annyit valóban el kell ismernünk, hogy az említett fogalmakat a modern matematikusok egyáltalán nem tartják titokzatosaknak, hanem fogékony elméjük által világosan felfogott és könnyen kezelhető tárgyaknak. Nem haboznak azt állítani, hogy ennek az új analízisnek a segítségével képesek behatolni magába a végtelenségbe, sőt kiterjeszthetik tudásukat a végtelenen túlra is, tehát módszerükkel nemcsak a végtelen, hanem – ahogy ők mondják – a végtelenül végtelen vagy a végtelenségek végtelensége is áttekinthetővé válik. Nyilatkozataiktól és szándékaiktól függetlenül azonban jogos a kérdés, hogy másokhoz hasonlóan, akiket a vizsgálódásaikban felhasznált szavak és kifejezések gyakran félrevezettek, vajon nem tévesztették-e meg, nem csalták-e lépre matematikusainkat is az általuk használt sajátos jelek, szimbólumok vagy műveletek. Mi sem könnyebb ugyanis, mint megfelelő jelölést találni az első-, másod-, harmad-, negyed- és sokadrendű fluxiók és infinitezimálisok számára úgy, hogy egyszerűen vég nélkül folytatjuk a következő szabályos sorozatot: $\dot{x}, \ddot{x}, \dddot{x}, \ddddot{x}$ stb., illetve $dx, ddx, dddx, ddddx$ stb. E kifejezések valóban világosak és áttekinthetők, s az elme számára semmiféle nehézséget nem okoz felfogni, hogy előállításukat minden megjelölhető határon túl folytatni lehet. Amint azonban fellebbentjük a fátylat és mögéje nézünk, amint félretéve a kifejezéseket arra törekszünk, hogy figyelmesen megvizsgáljuk magukat a dolgokat, amelyeket a feltevés szerint kifejeznek vagy jelölnek, akkor csupán ürességet, sötétséget és zűrzavart találunk; sőt ha nem tévedek: egyenesen képtelenségekre és ellentmondásokra bukkanunk. Hogy valóban ez-e a helyzet, annak megvizsgálását és megítélését gondolkodó olvasóimra bízom.

IX. Having considered the Object, I proceed to consider the Principles of this new Analysis by Momentums, Fluxions, or Infinitesimals; wherein if it shall appear that your capital Points, upon which the rest are supposed to depend, include Error and false Reasoning; it will then follow that you, who are at a loss to conduct your selves, cannot with any decency set up for guides to other Men. The main Point in the method of Fluxions is to obtain the Fluxion or Momentum of the Rectangle or Product of two indeterminate Quantities. Inasmuch as from thence are derived Rules for obtaining the Fluxions of all other Products and Powers; be the Coefficients or the Indexes what they will, integers or fractions, rational or surd. Now this fundamental Point one would think should be very clearly made out, considering how much is built upon it, and that its Influence extends throughout the whole Analysis. But let the Reader judge. This is given for Demonstration.(2) Suppose the Product or Rectangle $AB$ increased by continual Motion: and that the momentaneous Increments of the Sides $A$ and $B$ are $a$ and $b$. When the Sides $A$ and $B$ were deficient, or lesser by one half of their Moments, the Rectangle was

$$ \overline{A-\frac{1}{2}a}\times \overline{B-\frac{1}{2}b}, $$i.e.,

$$ AB-\frac{1}{2}aB-\frac{1}{2}bA+\frac{1}{4}ab. $$And as soon as the Sides $A$ and $B$ are increased by the other two halves of their Moments, the Rectangle becomes

$$ \overline{A+\frac{1}{2}a}\times \overline{B+\frac{1}{2}b} $$or

$$ AB+\frac{1}{2}aB+\frac{1}{2}bA+\frac{1}{4}ab. $$From the latter Rectangle subduct the former, and the remaining Difference will be $aB+bA$. Therefore the Increment of the Rectangle generated by the intire Increments $a$ and $b$ is $aB+bA$. Q.E.D. But it is plain that the direct and true Method to obtain the Moment or Increment of the Rectangle $AB$, is to take the Sides as increased by their whole Increments, and so multiply them together, $A + a$ by $B+b$, the Product whereof $AB+aB+bA+ab$ is the augmented Rectangle; whence if we subduct $AB$, the Remainder $aB+bA+ab$ will be the true Increment of the Rectangle, exceeding that which was obtained by the former illegitimate and indirect Method by the Quantity $ab$. And this holds universally be the Quantities $a$ and $b$ what they will, big or little, Finite or Infinitesimal, Increments, Moments, or Velocities. Nor will it avail to say that $ab$ is a Quantity exceeding small: Since we are told that in rebus mathematicis errores quam minimi non sunt contemnendi.(3)

9. Megvizsgálván a momentumok, fluxiók vagy infinitezimálisok újsütetű analízisének tárgyát, a továbbiakban rátérek elveinek vizsgálatára, amelynek során, ha majd kiviláglik, hogy az egész építmény alapjául szolgáló tételek tévedést és hamis okoskodást rejtenek, nyilvánvalóvá válik, hogy Önök, uraim, akik önmagukat is alig tudják irányítani, nem vállalkozhatnak becsülettel mások kalauzolására. A fluxiók módszerében a legfőbb feladat meghatározni egy téglalap vagyis két meghatározatlan mennyiség szorzatának fluxióját vagy momentumát; ebből ugyanis szabályokat vezetnek le, amelyek segítségével megállapítható bármilyen szorzat vagy hatvány fluxiója, függetlenül attól, hogy az együtthatók vagy kitevők egészek-e vagy törtek, racionálisak-e vagy irracionálisak. Mármost úgy vélné az ember, hogy ezt a fundamentális tételt rendkívül világosan fogalmazzák meg, mivel annyi minden épül rá, és következményei az egész analízisre kiterjednek. De inkább ítéljen az olvasó. Íme a tétel bizonyítása:3 tegyük fel, hogy az $AB$ szorzat vagy téglalap folytonos mozgással növekszik, és hogy az $A$ és $B$ oldalak pillanatnyi növekménye $a$ és $b$. Ha az $A$ és $B$ oldalak momentumaik felével megrövidülnének, azaz kisebbek lennének, akkor a téglalap területe:

$$ A-\frac{1}{2}a\times B-\frac{1}{2}b $$tehát

$$ AB-\frac{1}{2}aB-\frac{1}{2}bA+\frac{1}{4}ab $$lenne. Ha pedig az $A$ és $B$ oldalak momentumaik felével megnőnek, akkor a téglalap területe:

$$ A+\frac{1}{2}a\times B+\frac{1}{2}b $$tehát:

$$ AB+\frac{1}{2}aB+\frac{1}{2}bA+\frac{1}{4}ab. $$Az utóbbi területből levonva az előbbit, a különbség: $aB + bA$. Ezért az $a$ és $b$ növekmények révén létrejövő növekmény téglalap területe: $aB+bA$. Q. e. d. Nyilvánvaló ezzel szemben, hogy a helyes és egyenes út az $AB$ téglalap növekményének meghatározására az, hogy a teljes növekményükkel megnagyobbított oldalakat egymással összeszorozzuk, tehát $A+a$-t $B+b$-vel, amikor is az eredmény $AB+aB+bA+ab$, s ez a megnövelt téglalap területe; ebből levonva az eredeti téglalap $AB$ területét, a maradék $aB+bA+ab$ lesz a téglalap valódi növekménye, s ez az $ab$ mennyiséggel nagyobb, mint a fentebbi közvetett és megengedhetetlen módon nyert érték. S ez egyetemes érvényű, bármilyenek legyenek is az $a$ és $b$ mennyiségek, kicsik vagy nagyok, végesek vagy infinitezimálisak, növekmények, momentumok vagy sebességek. És mit sem ér azt mondani, hogy az $ab$ rendkívül kicsiny mennyiség, mert ahogy éppen Önök hangoztatják: in rebus mathematicis errores quam minimi non sunt contemnendi.4

X. Such reasoning as this for Demonstration, nothing but the obscurity of the Subject could have encouraged or induced the great Author of the Fluxionary Method to put upon his Followers, and nothing but an implicit deference to Authority could move them to admit. The Case indeed is difficult. There can be nothing done till you have got rid of the Quantity $ab$. In order to this the Notion of Fluxions is shifted: it is placed in various Lights: Points which should be as clear as first Principles are puzzled; and Terms which should be steadily used are ambiguous. But notwithstanding all this address and skill the point of getting rid of $ab$ cannot be obtained by legitimate reasoning. If a Man by Methods, not geometrical or demonstrative, shall have satisfied himself of the usefulness of certain Rules; which he afterwards shall propose to his Disciples for undoubted Truths; which he undertakes to demonstrate in a subtile manner, and by the help of nice and intricate Notions; it is not hard to conceive that such his Disciples may, to save themselves the trouble of thinking, be inclined to confound the usefulness of a Rule with the certainty of a Truth, and accept the one for the other; especially if they are Men accustomed rather to compute than to think; earnest rather to go on fast and far, than solicitous to set out warily and see their way distinctly.

10. Csakis a tárgy zavarossága indíthatta és bátoríthatta fel a fluxiós módszer nagy hírű szerzőjét arra, hogy ilyesfajta okoskodást bizonyításként kényszerítsen követőire, akiket csakis a hallgatólagos tekintélytisztelet vehetett rá arra, hogy ezt elfogadják. A helyzet valóban nehéz. Egyetlen lépést sem lehet tenni, amíg meg nem szabadulnak az $ab$ mennyiségtől. Ennek érdekében megváltoztatják és különböző megvilágításokba helyezik a fluxiók fogalmát, összezavarva olyan tételeket, amelyeknek mint alapelveknek világosaknak kellene lenniük, és kétértelműen alkalmazva a szigorúan azonos értelemben használandó kifejezéseket. De még e mesterkedések és ügyeskedések ellenére sem lehet elfogadható érveléssel megszabadulni az $ab$-től. Ha valaki nem geometriai, azaz nem demonstratív módszerrel meggyőződik bizonyos szabályok használhatóságáról, s ezeket azután tanítványainak megingathatatlan igazságokként ajánlja, miközben még bonyolult és tetszetős fogalmak segítségével ravasz módon bizonyítani is igyekszik őket, akkor nem nehéz megértenünk, hogy e tanítványok, megkímélve magukat a gondolkodás fáradságától, hajlani fognak arra, hogy e szabályok hasznosságát igazságuk bizonyosságával tévesszék össze, s beérjék az egyikkel a másik helyett; kiváltképpen, ha inkább számoláshoz, mint gondolkodáshoz szokott emberek, akik gyorsan és messzire akarnak jutni, mit sem törődve azzal, hogy világosan lássák az utat és körültekintően járjanak el.

XI. The Points or meer Limits of nascent Lines are undoubtedly equal, as having no more magnitude one than another, a Limit as such being no Quantity. If by a Momentum you mean more than the very initial Limit, it must be either a finite Quantity or an Infinitesimal. But all finite Quantities are expressly excluded from the Notion of a Momentum. Therefore the Momentum must be an Infinitesimal. And indeed, though much Artifice hath been employ’d to escape or avoid the admission of Quantities infinitely small, yet it seems ineffectual. For ought I see, you can admit no Quantity as a Medium between a finite Quantity and nothing, without admitting Infinitesimals. An Increment generated in a finite Particle of Time, is it self a finite Particle; and cannot therefore be a Momentum. You must therefore take an Infinitesimal Part of Time wherein to generate your Momentum. It is said, the Magnitude of Moments is not considered: And yet these same Moments are supposed to be divided into Parts. This is not easy to conceive, no more than it is why we should take Quantities less than $A$ and $B$ in order to obtain the Increment of $AB$, of which proceeding it must be owned the final Cause or Motive is very obvious; but it is not so obvious or easy to explain a just and legitimate Reason for it, or shew it to be Geometrical.

11. A születőben levő vonalak végpontjai vagy határai kétségkívül egyenlőek: egyik sem nagyobb, mint a másik, mivel a határ mint olyan nem mennyiség. Ha a momentumon mást értünk, mint magát a kezdeti határt, akkor ez vagy egy véges mennyiség lesz, vagy egy infinitezimális. De minden véges mennyiség határozottan ki van zárva a momentum fogalmából. Ezért a momentumnak infinitezimálisnak kell lennie. És valóban, bár sokféle fogáshoz folyamodtak a végtelenül kicsiny mennyiségek bevezetésének elkerülésére, egyik sem tűnik hatásosnak. Mert úgy látom, nem lehet bevezetni egy véges mennyiség és a semmi közé olyan közbülső mennyiséget, amely ne volna infinitezimális. Az időnek egy véges részecskéjében keletkező növekmény maga is véges részecske, így tehát nem lehet momentum. Az Önök momentuma, csak az időnek egy infinitezimális részében keletkezhet. Önök azt mondják, hogy a momentumok nagyságát figyelmen kívül hagyják, mégis feltételezik, hogy e momentumok részekre oszthatók. Ezt semmivel sem könnyebb felfogni, mint azt, hogy miért kell $A$-nál és $B$-nél kisebb mennyiségeket felvennünk, amikor az $AB$ növekményének meghatározásáról van szó; az persze igaz, hogy ennek az eljárásnak a célja és indítéka teljesen nyilvánvaló, de az már nem annyira nyilvánvaló és nem fejthető ki egykönnyen, hogy miképpen lehetne helyes és érvényes okát adni vagy geometriai jellegét bizonyítani.

XII. From the foregoing Principle so demonstrated, the general Rule for finding the Fluxion of any Power of a flowing Quantity is derived.(4) But, as there seems to have been some inward Scruple or Consciousness of defect in the foregoing Demonstration, and as this finding the Fluxion of a given Power is a Point of primary Importance, it hath therefore been judged proper to demonstrate the same in a different manner independent of the foregoing Demonstration. But whether this other Method be more legitimate and conclusive than the former, I proceed now to examine; and in order thereto shall premise the following Lemma. “If with a View to demonstrate any Proposition, a certain Point is supposed, by virtue of which certain other Points are attained; and such supposed Point be it self afterwards destroyed or rejected by a contrary Supposition; in that case, all the other Points, attained thereby and consequent thereupon, must also be destroyed and rejected, so as from thence forward to be no more supposed or applied in the Demonstration.” This is so plain as to need no Proof.

12. Az említett és ilyen módon bizonyított alapelvből vezetik le azt az általános szabályt, amellyel egy fluens mennyiség tetszőleges hatványának fluxióját megtalálhatjuk.5 De mivel úgy látszik, az ismertetett bizonyítást illetően valamilyen belső aggály támadt, vagy tudatára ébredtek a gondolatmenet fogyatékosságának, holott a szabály, amely egy adott hatvány fluxiójának meghatározására szolgál, elsőrendűen fontos, helyénvalónak vélték ugyanezt másképpen, az említett bizonyítástól függetlenül is bebizonyítani. De hogy ez a másféle módszer jogosabb és meggyőzőbb-e, mint az előző, azt most fogom megvizsgálni. Ennek érdekében hadd bocsássam előre a következő segédtételt: „Ha egy állítás bizonyítása céljából felveszünk valamely tételt, amelynek révén azután más tételekhez jutunk, és ha a későbbiekben a kiindulásként felvett tételt elvetjük s egy vele ellentétes tételt veszünk fel, akkor az elvetett tétel összes korábban levont következményeit is fel kell adnunk és el kell vetnünk, nem használhatjuk fel őket többé a bizonyítás folyamán.” Ez oly nyilvánvaló, hogy nem szorul igazolásra.

XIII. Now the other Method of obtaining a Rule to find the Fluxion of any Power is as follows. Let the Quantity $x$ flow uniformly, and be it proposed to find the Fluxion of $x^{n}$. In the same time that $x$ by flowing becomes $x+o$, the Power $x^{n}$ becomes $\overline{x+o} \text{|}^{ \text{ } n }$, i.e. by the Method of infinite Series

$$ { x }^{ n }+no{ x }^{ n-1 }+\frac { nn-n }{ 2 } oo{ x }^{ n-2 }+ \textit &c.$$and the Increments

$$ o \text { and } no{ x }^{ n-1 }+\frac { nn-n }{ 2 } oo{ x }^{ n-2 }+ \textit &c.$$are to one another as

$$ 1 \text { to } n{ x }^{ n-1 }+\frac { nn-n }{ 2 } o{ x }^{ n-2 }+ \textit &c.$$Let now the Increments vanish, and their last Proportion will be 1 to $nx^{n-1}$. But it should seem that this reasoning is not fair or conclusive. For when it is said, let the Increments vanish, i.e. let the Increments be nothing, or let there be no Increments, the former Supposition that the Increments were something, or that there were Increments, is destroyed, and yet a Consequence of that Supposition, i.e. an Expression got by virtue thereof, is retained. Which, by the foregoing Lemma, is a false way of reasoning. Certainly when we suppose the Increments to vanish, we must suppose their Proportions, their Expressions, and every thing else derived from the Supposition of their Existence to vanish with them.

13. A tetszőleges hatvány fluxiójánák meghatározására szolgáló szabály bizonyításának másik módszere mármost a következő: legyen az $x$ mennyiség egyenletesen fluens, a feladat pedig $x^{n}$ fluxiójának megtalálása. Amíg az $x$ mennyiség $x+0$-ra nő, ugyanannyi idő alatt az $x^{n}$ hatvány $(x+0)^{n}$ mennyiséggé változik, azaz a végtelen sorok módszerével:

$$ { x }^{ n }+n0{ x }^{ n-1 }+\frac { nn-n }{ 2 } 0{ x }^{ n-2 }+ \text{stb.}$$és a növekmények:

$$ 0 \text { and } n0{ x }^{ n-1 }+\frac { nn-n }{ 2 } 00{ x }^{ n-2 }+ \text{stb.}$$úgy aránylanak egymáshoz, mint:

$$ 1 \text { to } n{ x }^{ n-1 }+\frac { nn-n }{ 2 } 0{ x }^{ n-2 }+ \text{stb.}$$Tegyük most fel, hogy a növekmények eltűnnek, és az eltűnés előtti utolsó arányuk ez lesz: 1 aránylik $nx^{n-1}$-hez. Ez az okoskodás nem látszik kifogástalannak és meggyőzőnek. Mert amikor azt mondjuk: „tegyük fel, hogy a növekmények eltűnnek”, azaz semmivé válnak, azaz egyáltalán nincsenek növekmények, akkor a korábbi feltevés, mely szerint vannak növekmények, megsemmisül, mégis fenntartjuk e feltevés következményét, vagyis azt a kifejezést, amelyet ennek a feltevésnek az alapján kaptunk. Ez azonban az említett segédtétel szerint hamis okoskodás. Ha ugyanis feltesszük, hogy a növekmények eltűnnek, akkor egyidejűleg azt is fel kell tennünk, hogy velük együtt arányaik is eltűnnek az őket tartalmazó kifejezésekkel és mindazzal, amit létezésük feltevéséből vezettünk le.

XIV. To make this Point plainer, I shall unfold the reasoning, and propose it in a fuller light to your View. It amounts therefore to this, or may in other Words be thus expressed. I suppose that the Quantity $x$ flows, and by flowing is increased, and its Increment I call $o$, so that by flowing it becomes $x+o$. And as $x$ increaseth, it follows that every Power of $x$ is likewise increased in a due Proportion. Therefore as $x$ becomes $x+o$, $x^{n}$ will become $\overline{x+o} \text{|}^{ \text{ } n }$: that is, according to the Method of infinite Series,

$$ { x }^{ n } +no{ x }^{ n-1 }+ \frac{ nn-n }{ 2 } oo{ x }^{ n-2 }+ \textit &c.$$And if from the two augmented Quantities we subduct the Root and the Power respectively, we shall have remaining the two Increments, to wit,

$$ o \text { and } no{ x }^{ n-1 }+\frac { nn-n }{ 2 } oo{ x }^{ n-2 }+ \textit &c.$$which Increments, being both divided by the common Divisor $o$, yield the Quotients

$$ 1 \text{ to } n{ x }^{ n-1 } +\frac{ nn-n }{ 2 } o{ x }^{ n-2 }+ \textit &c.$$which are therefore Exponents of the Ratio of the Increments. Hitherto I have supposed that $x$ flows, that $x$ hath a real Increment, that $o$ is something. And I have proceeded all along on that Supposition, without which I should not have been able to have made so much as one single Step. From that Supposition it is that I get at the Increment of $x^{n}$, that I am able to compare it with the Increment of $x$, and that I find the Proportion between the two Increments. I now beg leave to make a new Supposition contrary to the first, i.e. I will suppose that there is no Increment of $x$, or that $o$ is nothing; which second Supposition destroys my first, and is inconsistent with it, and therefore with every thing that supposeth it. I do nevertheless beg leave to retain $nx^{n-1}$, which is an Expression obtained in virtue of my first Supposition, which necessarily presupposeth such Supposition, and which could not be obtained without it: All which seems a most inconsistent way of arguing, and such as would not be allowed of in Divinity.

14. E pontot még jobban megvilágítandó, kifejtem és teljesebb megvilágításban állítom Önök elé az iménti gondolatmenetet. Más szóvakkal kifejezve tehát ez a következőképpen hangzik: feltételezzük, hogy az $x$ fluens mennyiség növekedik, gyarapodását pedig $0$-val jelöljük; eszerint $x$ a növekedés folytán $x+0$ értékűvé válik. Minthogy pedig $x$ nő, vele nő minden hatványa, megfelelő mértékben. Ezért amint $x$ átalakul $x+0$-vá, $x^{n}$ átalakul $(x+0)^{n}$-né; a végtelen sorok módszere szerint tehát:

$$ { x }^{ n }+n0{ x }^{ n-1 }+\frac { nn-n }{ 2 } 0{ x }^{ n-2 }+ \text{stb.}$$Mármost, ha a két megnövelt mennyiségből levonjuk a hatványalapot, illetve a hatványt, akkor a következő növekményt kapjuk:

$$ 0 \text{ and } n0{ x }^{ n-1 }+\frac { nn-n }{ 2 } 00{ x }^{ n-2 }+ \text{stb.}$$s ha e két növekmény mindegyikét elosztjuk $0$ közös osztóval, a következő hányadosokat kapjuk:

$$ 1 \text{ to } n{ x }^{ n-1 }+\frac { nn-n }{ 2 } 0{ x }^{ n-2 }+ \text{stb.,}$$amelyek ennélfogva a növekmények arányát állítják elő. Mindeddig feltételeztem, hogy $x$ fluens, tehát valódi növekménye van, hogy $0$ nem semmi, hanem valami. Végig e feltevés alapján jártam el, hiszen e nélkül egyetlen lépést sem tehettem volna. Ennek alapján állítottam elő $x^{n}$ növekményét, amelyet össze tudok hasonlítani $x$ növekményével, hogy meghatározzam a két növekmény arányát. Most azonban engedélyt kérek egy új, az előzővel ellentétes feltevésre, azaz arra, hogy feltegyem: $x$-nek nincs növekménye, tehát a $0$ semmi. Ez az újabb feltevés megsemmisíti az előzőt, ellentmond neki, tehát mindannak, ami belőle következik: Mindazonáltal engedélyt kérek arra, hogy megtartsam $nx^{n-1}-et, amelyet előző feltevésem alapján nyertem, s amely ezért szükségszerűen előfeltételezi ezt az előző feltevést, nélküle nem is lett volna levezethető. Mindez fölöttébb ellentmondásos érvetésnek tűnik, és a teológiában egyáltalán nem lenne megengedhető.

XV. Nothing is plainer than that no just Conclusion can be directly drawn from two inconsistent Suppositions. You may indeed suppose any thing possible: But afterwards you may not suppose any thing that destroys what you first supposed. Or if you do, you must begin de novo. If therefore you suppose that the Augments vanish, i.e. that there are no Augments, you are to begin again, and see what follows from such Supposition. But nothing will follow to your purpose. You cannot by that means ever arrive at your Conclusion, or succeed in, what is called by the celebrated Author, the Investigation of the first or last Proportions of nascent and evanescent Quantities, by instituting the Analysis in finite ones. I repeat it again: You are at liberty to make any possible Supposition: And you may destroy one Supposition by another: But then you may not retain the Consequences, or any part of the Consequences of your first Supposition so destroyed. I admit that Signs may be made to denote either any thing or nothing: And consequently that in the original Notation $x+o$, $o$ might have signified either an Increment or nothing. But then which of these soever you make it signify, you must argue consistently with such its Signification, and not proceed upon a double Meaning: which to do were a manifest Sophism. Whether you argue in Symbols or in Words, the Rules of right Reason are still the same. Nor can it be supposed, you will plead a Privilege in Mathematics to be exempt from them.

15. Mi sem nyilvánvalóbb, mint hogy két egymásnak ellentmondó feltevésből nem vonható le helyes következmény. Mert bármit feltételezhetünk, ami csak lehetséges, de azután már semmit sem szabad feltételezni, ami az első feltevést megsemmisíti; vagy ha valaki mégis ezt teszi, mindent de novo kell kezdenie. Ha tehát Önök felteszik, hogy a növekmények eltűnnek, azaz nincsenek növekmények, akkor vissza kell térniük a kiindulóponthoz, és megnézni, mi következik ebből a feltevésből. Semmiképpen sem olyasmi, ami megfelelne célfáiknak. Ily módon soha nem jutnak el a kívánt következményekhez, és nem járhatnak sikerrel abban, amit e módszer hírneves szerzője így nevezett: a születőben és eltűnőben levő mennyiségek első vagy végső arányainak vizsgálata a véges mennyiségek analízisének mintájára. Ismétlem: szabadságukban áll bármit feltételezni, sőt az egyik feltevést egy masikkal helyettesíteni, de ebben az esetben nem tarthatják fenn az első, megsemmisített feltevés következményeit, sem pedig ezek valamelyik részét. Megengedem, hogy be lehet vezetni olyan jelöléseket, amelyek valamit vagy semmit sem jelölnek; következésképpen, hogy $x+0$ jelölhetne egy növekményt vagy éppen semmit. De amint eldöntötték, hogy voltaképpen mit jelöl, ragaszkodniuk kell hozzá az érvelés folyamán, nem használhatják kettős értelemben; nyílt szofisztika volna ezt tenni. Akár szavakban, akár jelekkel folyjék is az érvelés, a helyes gondolkodás szabályai ugyanazok. És Önök feltehetően nem formálnak jogot arra, hogy a matematika kivétel legyen a szabályok alól.

XVI. If you assume at first a Quantity increased by nothing, and in the Expression $x+o$, $o$ stands for nothing, upon this Supposition as there is no Increment of the Root, so there will be no Increment of the Power; and consequently there will be none except the first, of all those Members of the Series constituting the Power of the Binomial; you will therefore never come at your Expression of a Fluxion legitimately by such Method. Hence you are driven into the fallacious way of proceeding to a certain Point on the Supposition of an Increment, and then at once shifting your Supposition to that of no Increment. There may seem great Skill in doing this at a certain Point or Period. Since if this second Supposition had been made before the common Division by $o$, all had vanished at once, and you must have got nothing by your Supposition. Whereas by this Artifice of first dividing, and then changing your Supposition, you retain 1 and $nx^{n-1}$. But, notwithstanding all this address to cover it, the fallacy is still the same. For whether it be done sooner or later, when once the second Supposition or Assumption is made, in the same instant the former Assumption and all that you got by it is destroyed, and goes out together. And this is universally true, be the Subject what it will, throughout all the Branches of humane Knowledge; in any other of which, I believe, Men would hardly admit such a reasoning as this, which in Mathematics is accepted for Demonstration.

16. Ha egy mennyiségről először felteszik, hogy nem növekedett semmivel, tehát az $x+0$ kifejezésben a $0$ a semmit jelöli, akkor a feltevés szerint a hatvány nem fog növekedni, ha az alap sem növekszik; következésképpen a binomiális kifejezés hatványsorának csak az első tagja fog nullától különbözni; tehát ezzel a módszerrel nem lehet elfogadhatóan eljutni a fluxió előállításához. Ezért azután Önök azt a téves utat választják, hogy egy ideig növekményt feltételeznek, azután pedig hirtelen átváltanak arra a feltevésre, hogy nincs növekmény. S úgy tetszik, ügyesen választják meg, mikor tegyék. Ha ugyanis a második feltevésre a $0$-val való osztás előtt kerülne sor, akkor egy csapásra minden eltűnne, és semmire sem mennének a feltevésükkel. Azzal a fogással viszont, hogy először végigosztanak $0$-val, s csak azután váltanak át a másik feltevésre, előáll az 1 és az $nx^{n-1}$. De bárhogyan igyekezzenek is palástolni, a hiba ugyanaz marad. Mert akár előbb, akár utóbb vezetik be a második feltevést, mihelyt megteszik, az előző feltevés és mindaz, amit ennek révén nyertek, tüstént megsemmisül. S ez egyetemesen igaz, bármiről legyen is szó az emberi tudás bármely ágában; úgy hiszem, egyetlen más tudományág sincsen, ahol megengedhetőnek tartanák az effajta okoskodást, amelyet a matematikában bizonyításnak fogadnak el.

XVII. It may not be amiss to observe, that the Method for finding the Fluxion of a Rectangle of two flowing Quantities, as it is set forth in the Treatise of Quadratures, differs from the abovementioned taken from the second Book of the Principles, and is in effect the same with that used in the calculus differentialis.(5) For the supposing a Quantity infinitely diminished and therefore rejecting it, is in effect the rejecting an Infinitesimal; and indeed it requires a marvellous sharpness of Discernment, to be able to distinguish between evanescent Increments and infinitesimal Differences. It may perhaps be said that the Quantity being infinitely diminished becomes nothing, and so nothing is rejected. But according to the received Principles it is evident, that no Geometrical Quantity, can by any division or subdivision whatsoever be exhausted, or reduced to nothing. Considering the various Arts and Devices used by the great author of the Fluxionary Method: in how many Lights he placeth his Fluxions: and in what different ways he attempts to demonstrate the same Point: one would be inclined to think, he was himself suspicious of the justness of his own demonstrations; and that he was not enough pleased with any one notion steadily to adhere to it. Thus much at least is plain, that he owned himself satisfied concerning certain Points, which nevertheless he could not undertake to demonstrate to others.(6) Whether this satisfaction arose from tentative Methods or Inductions; which have often been admitted by Mathematicians (for instance by Dr. Wallis in his Arithmetic of Infinites) is what I shall not pretend to determine. But, whatever the Case might have been with respect to the Author, it appears that his Followers have shewn themselves more eager in applying his Method, than accurate in examining his Principles.

17. Helyénvalónak látszik az az észrevétel, hogy a két fluens mennyiségből keletkező téglalap fluxiójának meghatározására A Görbék Kvadratúrájáról szóló Értekezés más módszert fejt ki, mint a Principia második könyve, amelyből a fentebb ismertetett eljárást vettük. Az Értekezésbeli módszer lényegében megegyezik a calculus differentialisban használt eljárással. Mert egy mennyiség végtelenül kicsinnyé válásának feltételezése és így elvetése lényegében egy infinitezimálisnak az elvetését jelenti; és valóban csodálatra méltó éleselméjűség szükséges ahhoz, hogy különbséget tegyünk az eltűnőben levő növekmények és az infinitezimális differenciák között. Mondhatják talán, hogy egy végtelenül kicsinnyé vált mennyiség semmivé lesz, s így semmi az, amit elvetünk. Az elfogódott alapelvek szerint azonban nyilvánvaló, hogy egy geometriai mennyiség részekre osztással vagy gyökvonással semmiképpen nem meríthető ki, nem tehető semmivé. Ha tekintetbe vesszük, hogy a fluxiós módszer jeles szerzője hányféle fortélyhoz és furfanghoz folyamodik, hányféle megvilágításba helyezi fluxióit, és hányféle módon próbálja bebizonyítani ugyanazt, akkor már-már hajlamosak vagyunk azt gondolni, hogy ő maga is gyanút fogott bizonyításainak helyességét illetően, és nem volt annyira elégedett az általa bevezetett fogalmakkal, hogy állhatatosan ragaszkodott volna hozzájuk. Annyi mindenesetre világos, hogy bizonyos pontokkal kapcsolatban elégedettnek mondta magát, mindazonáltal ezeket sem volt képes mások számára elfogadhatóan bebizonyítani.6 Hogy ez az elégedettség kísérleti módszerek vagy indukciók alkalmazásából fakadt-e, nem szándékozom eldönteni. Ilyen módszereket egyébként a matematikusok is gyakran elfogadnak (így dr. Wallis a Végtelenek aritmetikájáról írott munkájában). De bárhogyan álljon is a helyzet a szerzővel, annyi bizonyos, hogy követői buzgóbbak voltak módszerének alkalmazásában, mint amennyire gondosak alapelveinek megvizsgálásában.

XVIII. It is curious to observe, what subtilty and skill this great Genius employs to struggle with an insuperable Difficulty; and through what Labyrinths he endeavours to escape the Doctrine of Infinitesimals; which as it intrudes upon him whether he will or no, so it is admitted and embraced by others without the least repugnance. Leibnitz and his followers in their calculus differentialis making no manner of scruple, first to suppose, and secondly to reject Quantities infinitely small: with what clearness in the Apprehension and justness in the reasoning, any thinking Man, who is not prejudiced in favour of those things, may easily discern. The Notion or Idea of an infinitesimal Quantity, as it is an Object simply apprehended by the Mind, hath been already considered.(7) I shall now only observe as to the method of getting rid of such Quantities, that it is done without the least Ceremony. As in Fluxions the Point of first importance, and which paves the way to the rest, is to find the Fluxion of a Product of two indeterminate Quantities, so in the calculus differentialis (which Method is supposed to have been borrowed from the former with some small Alterations) the main Point is to obtain the difference of such Product. Now the Rule for this is got by rejecting the Product or Rectangle of the Differences. And in general it is supposed, that no Quantity is bigger or lesser for the Addition or Subduction of its Infinitesimal: and that consequently no error can arise from such rejection of Infinitesimals.

18. Érdekes megfigyelni, milyen éleselméjűen és ügyesen igyekszik ez a nagy szellem megbirkózni a leküzdhetetlen nehézségekkel; miféle labirintusba veszi be magát, hogy megmeneküljön az infinitezimálisok tanától, amely őt még erővel keríti hatalmába, akár akarja, akár nem, de mások már a legkisebb ellenérzés nélkül fogadják el és teszik magukévá. Leibniznek és követőinek semmiféle aggályt nem okoz, hogy calculus differentialisukban először feltételezzék, azután pedig elvessék a végtelenül kicsiny mennyiségeket; s hogy eljárásuk mennyiben áttekinthető, gondolkodásmódjuk mennyiben helyes, azt minden gondolkodó ember könnyen megítélheti, ha nincsenek ebben a kérdésben előítéletei. Az infinitezimális mennyiség fogalmát vagy ideáját, mint az elme által egyszerűen felfogott tárgyat, már korábban megvizsgáltuk. Most csupán azt a módszert veszem szemügyre, amellyel megszabadulnak tőlük, méghozzá minden teketória nélkül. Ahogyan a fluxiók elméletében a legfontosabb teendő, amely minden továbbinak az útját egyengeti, két meghatározatlan mennyiség szorzatának fluxióját megtalálni, úgy a calculus differentialisban (amelyet a feltevések szerint kis módosításokkal az előbbi módszerből kölcsönöztek) a legalapvetőbb dolog e szorzat differenciájának előállítása. Az e célra szolgáló szabály az, hogy elhanyagolják a differenciák szorzatát vagyis téglalapját. És általánosságban felteszik, hogy egy mennyiség nem lesz nagyobbá vagy kisebbé infinitezimálisainak hozzáadásával vagy levonásával, következésképpen semmi hiba nem származhat abból, ha az infinitezimálisokat elhanyagolják.

XIX. And yet it should seem that, whatever errors are admitted in the Premises, proportional errors ought to be apprehended in the Conclusion, be they finite or infinitesimal: and that therefore the ἀκρίβεια of Geometry requires nothing should be neglected or rejected. In answer to this you will perhaps say, that the Conclusions are accurately true, and that therefore the Principles and Methods from whence they are derived must be so too. But this inverted way of demonstrating your Principles by your Conclusions, as it would be peculiar to you Gentlemen, so it is contrary to the Rules of Logic. The truth of the Conclusion will not prove either the Form or the Matter of a Syllogism to be true: inasmuch as the Illation might have been wrong or the Premises false, and the Conclusion nevertheless true, though not in virtue of such Illation or of such Premises. I say that in every other Science Men prove their Conclusions by their Principles, and not their Principles by the Conclusions. But if in yours you should allow your selves this unnatural way of proceeding, the Consequence would be that you must take up with Induction, and bid adieu to Demonstration. And if you submit to this, your Authority will no longer lead the way in Points of Reason and Science.

19. Mégis úgy tűnik, hogy bármilyen hibák forduljanak elő a premisszákban, velük arányos hibákat kell majd észlelni a konklúzióban is, legyenek akár végesek, akár infinitezimálisak; ezért a geometriai ἀκρίβεια követelményei szerint semmit sem szabad elhanyagolni vagy figyelmen kívül hagyni. Meglehet, erre Önök azt válaszolják, hogy a következmények pontosak és igazak, tehát azoknak az alapelveknek és módszereknek, amelyekkel levezettük őket, szintén igazaknak kell lenniük. Ám ez a fordított eljárás, amely az alapelveket következményeikkel bizonyítja, ha Önökre tán jellemző is, uraim, ellentétes a logika szabályával. A következmény igazsága nem bizonyítja, hogy a szillogizmus akár formálisan, akár materiálisan helyes volna; amennyiben az is lehetséges, hogy a következtetés helytelen vagy a premisszák hamisak, de a konklúzió mégis igaz, noha nem a következtetés vagy a premisszák jóvoltából. Én azt állítom, hogy az emberek minden más tudományban a következményeket bizonyítják az alapelvekkel s nem az alapelveket a következményekkel. De ha Önök a saját tudományukban megengedik maguknak e természetellenes eljárásmódot, akkor az Indukcióval kell szövetkezniük és búcsút mondaniuk a Demonstrációnak. Ha pedig ebbe az irányba térnek, nem lesznek többé illetékesek, hogy utat mutassanak az Ész és a Tudomány dolgaiban.

XX. I have no Controversy about your Conclusions, but only about your Logic and Method. How you demonstrate? What Objects you are conversant with, and whether you conceive them clearly? What Principles you proceed upon; how sound they may be; and how you apply them? It must be remembred that I am not concerned about the truth of your Theorems, but only about the way of coming at them; whether it be legitimate or illegitimate, clear or obscure, scientific or tentative. To prevent all possibility of your mistaking me, I beg leave to repeat and insist, that I consider the Geometrical Analyst as a Logician, i.e. so far forth as he reasons and argues; and his Mathematical Conclusions, not in themselves, but in their Premises; not as true or false, useful or insignificant, but as derived from such Principles, and by such Inferences. And forasmuch as it may perhaps seem an unaccountable Paradox, that Mathematicians should deduce true Propositions from false Principles, be right in the Conclusion, and yet err in the Premises; I shall endeavour particularly to explain why this may come to pass, and shew how Error may bring forth Truth, though it cannot bring forth Science.

20. Nem a konklúzióikat vitatom, csak a logikájukat és a módszerüket. Hogyan is bizonyítanak Önök? Milyen tárgyakkal foglalkoznak, és vajon világosan fogják-e fel őket? Milyen alapelvek szerint járnak el; mennyire szilárdak ezek, és hogyan használják fel őket? Emlékeztetnem kell rá, hogy nem tantételeik igazságát firtatom, hanem csupán azt vizsgálom, hogyan jutottak hozzájuk, törvényes vagy törvénytelen úton, áttekinthető vagy zavaros módon, tudományosan vagy találomra. S hogy a félreértés lehetőségét is elkerüljem, kérem, engedjék ismételten hangsúlyoznom, hogy az analitikus geométert logikusnak tekintem, azaz olyan egyénnek, aki érvel és indokol; matematikai konklúzióit sem önmagukban veszem szemügyre, hanem premisszáikban; nem az érdekel, hogy igazak-e vagy hamisak, használhatók vagy jelentés nélküliek, hanem az, hogy milyen alapelvekből és hogyan vannak levezetve. És miután talán megmagyarázhatatlan paradoxonnak tűnik, hogy matematikusok hogyan vezetnek le igaz tételeket hamis alapelvekből, hogyan lehet igazuk a következményben, ha tévedtek a premisszákban, kiváltképpen arra törekszem majd, hogy megvilágítsam, hogyan lehetséges ez, megmutassam, hogyan szülhet a tévedés igazságot, jóllehet tudományt nem.

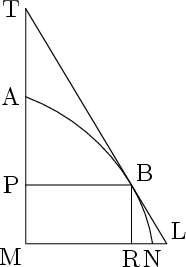

XXI. In order therefore to clear up this Point, we will suppose for instance that a Tangent is to be drawn to a Parabola, and examine the progress of this Affair, as it is performed by infinitesimal Differences.

21. E pont megvilágítása érdekében tegyük fel, hogy érintőt szerkesztünk egy parabolához, és vizsgáljuk meg, hogyan történik ez az infinitezimális differenciák alkalmazásával.

Let $AB$ be a Curve, the Abscisse $AP=x$, the Ordinate $PB=y$, the Difference of the Abscisse $PM=dx$, the Difference of the Ordinate $RN=dy$. Now by supposing the Curve to be a Polygon, and consequently $BN$, the Increment or Difference of the Curve, to be a straight Line coincident with the Tangent, and the differential Triangle $BRN$ to be similar to the triangle $TPB$ the Subtangent $PT$ is found a fourth Proportional to $RN:RB:PB$: that is to $dy:dx:y$. Hence the Subtangent will be

$$ \frac{ydx}{dy}. $$But herein there is an error arising from the aforementioned false supposition, whence the value of $PT$ comes out greater than the Truth: for in reality it is not the Triangle $RNB$ but $RLB$ which is similar to $PBT$, and therefore (instead of $RN$) $RL$ should have been the first term of the Proportion, i.e. $RN+NL$, i.e. $dy+z$: whence the true expression for the Subtangent should have been

$$ \frac{ydx}{dy+z}. $$There was therefore an error of defect in making $dy$ the divisor: which error was equal to $z$, i.e. $NL$ the Line comprehended between the Curve and the Tangent. Now by the nature of the Curve $yy=px$, supposing $p$ to be the Parameter, whence by the rule of Differences $2ydy=pdx$ and

$$ dy=\frac{pdx}{2y}. $$But if you multiply $y+dy$ by it self, and retain the whole Product without rejecting the Square of the Difference, it will then come out, by substituting the augmented Quantities in the Equation of the Curve, that

$$ dy=\frac{pdx}{2y}-\frac{dydy}{2y} $$truly. There was therefore an error of excess in making

$$ dy=\frac{pdx}{2y}, $$which followed from the erroneous Rule of Differences. And the measure of this second error is

$$ \frac{dydy}{2y}=z. $$Therefore the two errors being equal and contrary destroy each other; the first error of defect being corrected by a second error of excess.

Legyen $AB$ a görbe, az abszcissza $PA=x$, az ordináta $PB=y$, az abszcissza differenciája $PM=dx$, az ordináta differenciája $RN=dy$. Mármost, ha a görbét sokszögnek tekintjük, következésképpen a görbe $BN$ növekményét olyan egyenesnek, amely egybeesik az érintővel, a $BRN$ differenciális háromszögét pedig a $TPB$ háromszöghöz hasonlónak, akkor a $PT$ szubtangens a negyedik arányos lesz az $RN:RB:PB$, azaz a $dy:dx:y$ aránypárban. Innen a szubtangens:

$$ \frac{ydx}{dy} $$lesz. Ebben az eredményben azonban az említett hamis feltevésből eredő hiba rejlik, s így $PT$ értéke nagyobbnak adódik, mint a helyes érték. Valójában ugyanis nem az $RNB$, hanem az $RLB$ háromszög hasonló a $PBT$-hez, és ezért ($RN$ helyett) $RL$-nek kellene az aránypár első tagjának lennie, azaz $RN + NL$, azaz $dy+z$; ezért a szubtangens igazi értéke

$$ \frac{ydx}{dy+z} $$lenne. Hibás volt tehát $dy$-t venni osztónak, mert az osztó valójában nagyobb, a hiba mértéke pedig éppen $z$, azaz $NL$, a görbe és az érintő közti szakasz. Mármost a görbe parabola lévén: $yy=px$, ahol $p$ a paraméter, s amiből a differenciák módszere alapján $2ydy=pdx$ és

$$ dy=\frac{pdx}{2y}. $$Ha most megszorozzuk $y+dy$-t önmagával, és megtartjuk az egész szorzatot, tehát nem hanyagoljuk el a differencia négyzetét, akkor a megnövelt mennyiségeket behelyettesítve a görbe egyenletébe, az adódik, hogy valójában

$$ dy=\frac{pdx}{2y}-\frac{dydy}{2y}. $$Előzőleg tehát a differenciák téves szabálya alapján hibát követtek el, nagyobbnak véve $dy$-t, mint amekkora, amikor úgy tekintették, hogy

$$ dy=\frac{pdx}{2y}. $$E második hiba mértéke:

$$ \frac{dydy}{2y}=z. $$A két hiba, mivel egyenlő és ellentétes előjelű, megsemmisíti egymást; az első hibát, amikor a szóban forgó mennyiséget kisebbnek vették, mint amekkora, kiegyenlítette a második hiba, amikor viszont nagyobbnak vették ugyanazt.

XXII. If you had committed only one error, you would not have come at a true Solution of the Problem. But by virtue of a twofold mistake you arrive, though not at Science, yet at Truth. For Science it cannot be called, when you proceed blindfold, and arrive at the Truth not knowing how or by what means. To demonstrate that $z$ is equal to

$$ \frac{dydy}{2y}, $$let $BR$ or $dx$ be $m$ and $RN$ or $dy$ be $n$. By the thirty third Proposition of the first Book of the Conics of Apollonius, and from similar Triangles, as $2x$ to $y$ so is $m$ to

$$ n+z=\frac{my}{2x}. $$Likewise from the Nature of the Parabola $yy+2yn+nn=xp+mp$, and $2yn+nn=mp$: wherefore

$$ \frac{2yn+nn}{p}=m: $$and because $yy=px$,

$$ \frac{yy}{p} $$will be equal to $x$. Therefore substituting these values instead of $m$ and $x$ we shall have

$$ n+z=\frac{my}{2x}=\frac{2yynp+ynnp}{2yyp}: $$i.e.

$$ n+z=\frac{2yn+nn}{2y}: $$which being reduced gives

$$ z=\frac{nn}{2y}=\frac{dydy}{2y}\enspace\enspace\textit{Q.E.D.} $$22. Ha tehát csak egyetlen hibát követtek volna el, nem jutottak volna helyes megoldáshoz. Kétszeres hiba révén azonban, ha nem is tudományhoz, de igazsághoz jutottak. Mivel nem nevezhető tudománynak, ha vaktában járnak el, és úgy jutnak igazsághoz, hogy nem is tudják, hogyan sikerült. Bebizonyítandó, hogy $z$ egyenlő

$$ \frac{dydy}{2y}\text{-nal}, $$legyen $BR$ azaz $dx=m$, és $RN$ azaz $dy=n$. Apollonius kúpszeletekről írott művének első könyvében a 33. tétel szerint és a hasonló háromszögek törvénye alapján: ahogy $2x$ aránylik $y$-hoz, úgy aránylik $m$ az

$$ n+z=\frac{my}{2x} \text{-hez.} $$A parabola egyenlete alapján: $yy+2yn+nn=xp+mp$ és $2yn+nn=mp$, ezért

$$ \frac{2yn+nn}{p}=m, $$és mivel $yy=px$, tehát

$$ \frac{yy}{p} $$egyenlő lesz $x$-szel. Ezeket az értékeket helyettesítve $x$ és $m$ helyébe:

$$ n+z=\frac{my}{2x}=\frac{2yynp+ynnp}{2yyp}, $$azaz:

$$ n+z=\frac{2yn+nn}{2y} $$adódik, amiből egyszerűsítve:

$$ z=\frac{nn}{2y}=\frac{dydy}{2y}. \enspace\enspace\text{Q.e.d.} $$XXIII. Now I observe in the first place, that the Conclusion comes out right, not because the rejected Square of $dy$ was infinitely small; but because this error was compensated by another contrary and equal error. I observe in the second place, that whatever is rejected, be it every so small, if it be real, and consequently makes a real error in the Premises, it will produce a proportional real error in the Conclusion. Your Theorems therefore cannot be accurately true, nor your Problems accurately solved, in virtue of Premises, which themselves are not accurate, it being a rule in Logic that Conclusio sequitur partem debiliorem. Therefore I observe in the third place, that when the Conclusion is evident and the Premises obscure, or the Conclusion accurate and the Premises inaccurate, we may safely pronounce that such Conclusion is neither evident nor accurate, in virtue of those obscure inaccurate Premises or Principles; but in virtue of some other Principles which perhaps the Demonstrator himself never knew or thought of. I observe in the last place, that in case the Differences are supposed finite Quantities ever so great, the Conclusion will nevertheless come out the same: inasmuch as the rejected Quantities are legitimately thrown out, not for their smallness, but for another reason, to wit, because of contrary errors, which destroying each other do upon the whole cause that nothing is really, though something is apparently thrown out. And this Reason holds equally, with respect to Quantities finite as well as infinitesimal, great as well as small, a Foot or a Yard long as well as the minutest Increment.

23. Elsősorban tehát arra hívom fel a figyelmet, hogy a végeredmény nem azért jött ki helyesen, mert a $dy$ elhanyagolt négyzete végtelenül kicsiny volt, hanem azért, mert az így elkövetett hibát egy másik, ugyanakkora és ellentétes irányú hibával kiegyenlítették. Másodsorban azt jegyzem meg, hogy ha valamit elhanyagolnak, legyen bármilyen kicsiny is, ha valóságos, és így reális hibát jelent a premisszákban, akkor egy ezzel arányos, valóságos hiba fog fellépni a konklúziókban is. Az Önök tantételei ezért nem lehetnek szabatosan igazak, és a problémáik sem oldhatók meg szabatosan olyan premisszák alapján, amelyek maguk sem szabatosak; logikai szabály ugyanis, hogy conclusio sequitur partem debiliorem.7 Harmadsorban ezért azt jegyzem meg, hogy amikor a konklúzió nyilvánvaló, bár a premisszák homályosak, vagy amikor a konklúzió pontos, noha a premisszák pontatlanok, akkor bízvást kijelenthetjük, hogy az ilyen konklúzió nem a homályos és pontatlan premisszák vagy alapelvek alapján evidens és pontos, hanem olyan más elvek következtében, amelyeknek esetleg az sem volt tudatában, aki a következtetést elvégezte. Végül pedig arra hívom fel a figyelmet, hogy abban az esetben is, ha a differenciákat bármilyen nagy, véges mennyiségeknek tartanánk, a végeredmény ugyanaz lenne, mivel az elhanyagolt mennyiségeket jogosan hagyták figyelmen kívül, bár nem a kicsinységük miatt, hanem más okból: azért, mert az ellentétes és egymást kiegyenlítő hibák miatt csupán a látszat szerint, nem pedig valóságosan hagytak figyelmen kívül bármit is. S ez az ok érvényes, akármekkora mennyiségekről legyen is szó: végesekről vagy infinitezimálisokról, nagyokról vagy kicsinyekről, egy láb vagy egy yard hosszú növekményekről csakúgy, mint a legparányibbakról.

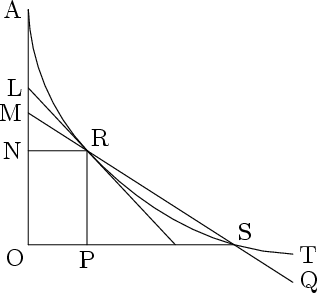

XXIV. For the fuller illustration of this Point, I shall consider it in another light, and proceeding in finite Quantities to the Conclusion, I shall only then make use of one Infinitesimal.

24. E pontot a teljesebb magyarázat kedvéért új fényben veszem szemügyre, és véges mennyiségeken át haladva a konklúzióig, csupán ott használok fel egy infinitezimálist.

Suppose the straight Line $MQ$ cuts the Curve $AT$ in the points $R$ and $S$. Suppose $LR$ a Tangent at the Point $R$, $AN$ the Abscisse, $NR$ and $OS$ Ordinates. Let $AN$ be produced to $O$, and $RP$ be drawn parallel to $NO$. Suppose $AN=x$, $NR=y$, $NO=v$, $PS=z$, the subsecant $MN=s$. Let the Equation $y=xx$ express the nature of the Curve: and supposing $y$ and $x$ increased by their finite Increments, we get $y+z=xx+2xv+vv$: whence the former Equation being subducted there remains $z=2xv+vv$. And by reason of similar Triangles

$$ PS:PR:NR:NM,\enspace\enspace\text{i.e.}\enspace\enspace z:v::y:s=\frac{vy}{z} $$wherein if for $y$ and $z$ we substitute their values, we get

$$ \frac{vxx}{2xv+vv}=s=\frac{xx}{2x+v}. $$And supposing $NO$ to be infinitely diminished, the subsecant $NM$ will in that case coincide with the subtangent $NL$, and $v$ as an Infinitesimal may be rejected, whence it follows that

$$ S=NL=\frac{xx}{2x}=\frac{x}{2}; $$which is the true value of the Subtangent. And since this was obtained by one only error, i.e. by once rejecting one only Infinitesimal, it should seem, contrary to what hath been said, that an infinitesimal Quantity or Difference may be neglected or thrown away, and the Conclusion nevertheless be accurately true, although there was no double mistake or rectifying of one error by another, as in the first Case. But if this Point be thoroughly considered, we shall find there is even here a double mistake, and that one compensates or rectifies the other. For in the first place, it was supposed, that when $NO$ is infinitely diminished or becomes an Infinitesimal, then the Subsecant $NM$ becomes equal to the Subtangent $NL$. But this is a plain mistake, for it is evident, that as a Secant cannot be a Tangent, so a Subsecant cannot be a Subtangent. Be the Difference ever so small, yet still there is a Difference. And if $NO$ be infinitely small, there will even then be an infinitely small Difference between $NM$ and $NL$. Therefore $NM$ or $s$ was too little for your supposition, (when you supposed it equal to $NL$) and this error was compensated by a second error in throwing out $v$, which last error made $s$ bigger than its true value, and in lieu thereof gave the value of the Subtangent. This is the true State of the Case, however it may be disguised. And to this in reality it amounts, and is at bottom the same thing, if we should pretend to find the Subtangent by having first found, from the Equation of the Curve and similar Triangles, a general Expression for all Subsecants, and then reducing the Subtangent under this general Rule, by considering it as the Subsecant when $v$ vanishes or becomes nothing.

Tegyük fel, hogy a $MQ$ egyenes az $R$ és $S$ pontban metszi az $AT$ görbét. Legyen $LR$ az $R$ pontbeli érintő, $AN$ az abszcissza, $NR$ és $OS$ ordináták. Hosszabbítsuk meg $AN$-t $O$-ig, és $RP$-t húzzuk meg párhuzamosan $NO$-val. Legyen $AN=x$, $NR=y$, $NO=v$, $PS=z$ és a szubszekáns $MN = s$. Az $y = xx$ egyenlet írja le a görbét. Növeljük most meg $x$-et és $y$-t véges növekményekkel, ekkor az egyenlet alapján: $y+z=xx+2xv+vv$, amiből levonva az eredeti egyenletet: $z=2xv+vv$. A hasonló háromszögek alapján:

$$PS:PR=NR:NM, \enspace\enspace \text{azaz} \enspace\enspace z:v=y:s,$$tehát

$$ \frac{vy}{z}=s, $$amelyben $y$ és $z$ helyére behelyettesítve a fenti értékeiket, azt kapjuk, hogy

$$ \frac{vxx}{2xv+vv}=s=\frac{xx}{2x+v}. $$Feltéve, hogy $NO$ végtelenül kicsinnyé válik, a szubszekáns $NM$ egybe fog esni $NL$-lel, a szubtangenssel, $v$-t pedig mint infinitezimálist elhanyagolhatjuk, amiből az adódik, hogy a szubtangens valódi értéke:

$$ S=NL=\frac{xx}{2x}=\frac{x}{2}. $$És mivel ezt az eredményt csak egy hiba elkövetése árán, azaz csupán egy infinitezimális elhanyagolásával nyertük, úgy tűnhet – ellentétben azzal, amit korábban mondtunk –, hogy egy infinitezimális mennyiség vagy differencia valóban elhanyagolható vagy elvethető, mert a végeredmény szabatosan igaz, bár nem követtünk el kettős hibát, azaz nem egyenlítettük ki az egyik hibát egy másikkal, mint az előző esetben. Ha azonban jobban szemügyre vesszük ezt az esetet, akkor azt fogjuk találni, hogy ebben is kettős hiba rejlik, s az egyik kiegyenlíti vagy helyrehozza a másikat. Mert először is feltettük, hogy amikor $NO$ végtelenül kicsinnyé vagyis infinitezimálissá válik, akkor az $NM$ szubszekáns egyenlővé válik az $NL$ szubtangenssel. Ez azonban félreérthetetlenül téves; nyilvánvaló ugyanis, hogy amiképpen egy szelő (szekáns) nem lehet érintő (tangens), úgy a szubszekáns nem lehet azonos a szubtangenssel. Bármilyen kicsiny legyen is köztük a különbség, mégis különbözőek lesznek. És ha $NO$ végtelenül kicsiny lesz, akkor is lesz egy végtelenül kicsiny különbség $NM$ és $NL$ között. Tehát $NM$, azaz $S$ túl kicsi volt ahhoz, hogy megfeleljen a feltevésüknek (amikor feltették, hogy egyenlő $NL$-lel), ezt a hibát azonban kiegyenlítették egy másikkal, amikor elvetették $v$-t, s ezzel $s$-t nagyobbnak tekintették valódi értékénél, így állt elő azután a szubtangens értéke. Ez a való helyzet, bárhogyan leplezzék is. Amit tesznek, az voltaképpen nem más, mint hogy a szubtangens előállítása céljából a görbe egyenlete és a hasonló háromszögek segítségével először előállítják az összes szubszekánsok általános formáját, azután pedig e szabály alapján a szubtangensét, miközben ezt olyan szubszekánsnak tekintik, amelynél $v$ eltűnik, semmivé válik.

XXV. Upon the whole I observe, First, that v can never be nothing so long as there is a secant. Secondly, that the same Line cannot be both tangent and secant. Thirdly, that when $v$ and $NO$(8) vanisheth, $PS$ and $SR$ do also vanish, and with them the proportionality of the similar Triangles. Consequently the whole Expression, which was obtained by means thereof and grounded thereupon, vanisheth when $v$ vanisheth. Fourthly, that the Method for finding Secants or the Expression of Secants, be it ever so general, cannot in common sense extend any further than to all Secants whatsoever: and, as it necessarily supposeth similar Triangles, it cannot be supposed to take place where there are not similar Triangles. Fifthly, that the Subsecant will always be less than the Subtangent, and can never coincide with it; which Coincidence to suppose would be absurd; for it would be supposing, the same Line at the same time to cut and not to cut another given Line, which is a manifest Contradiction, such as subverts the Hypothesis and gives a Demonstration of its Falshood. Sixthly, if this be not admitted, I demand a Reason why any other apagogical Demonstration, or Demonstration ad absurdum should be admitted in Geometry rather than this: Or that some real Difference be assigned between this and others as such. Seventhly, I observe that it is sophistical to suppose $NO$ or $RP$, $PS$, and $SR$ to be finite real Lines in order to form the Triangle $RPS$, in order to obtain Proportions by similar Triangles; and afterwards to suppose there are no such Lines, nor consequently similar Triangles, and nevertheless to retain the Consequence of the first Supposition, after such Supposition hath been destroyed by a contrary one. Eighthly, That although, in the present case, by inconsistent Suppositions Truth may be obtained, yet that such Truth is not demonstrated: That such Method is not conformable to the Rules of Logic and right Reason: That, however useful it may be, it must be considered only as a Presumption, as a Knack, an Art, rather an Artifice, but not a scientific Demonstration.