But to return to Van Gogh and the start of his career. Having largely

taught himself to draw and paint, he had had little contact with colleagues,

and living in a remote village in Brabant did not improve his prospects

of interesting encounters either. Thus Vincent’s life was a fairly isolated

one. It was a stroke of luck that he was familiar with the latest developments

in Paris. Theo van Gogh was working there as an art dealer and sent magazines

and the latest books, such as those of Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, to

Brabant. These two brothers, whose reputation rests especially on their

diaries, considered themselves the discoverers of the Japanese art of printmaking.

The visit they made in 1861 to the Von Siebold collection in the Rijks Japansch

Museum in Leiden is proof of their serious interest. In their novels Japanese

art is often mentioned and Van Gogh, who was an avid reader, often referred

to these authors whom he admired. The Goncourts’ enthusiasm for Japanese

prints undoubtedly aroused his interest.

The first mention of Japanese art in his letters was in November 1885,

when Vincent, writing from Antwerp where he had just arrived, told Theo

that he felt at home in his small room because he had hung some Japanese

prints there: ’You know those little women’s figures in gardens, or on

the beach, horsemen, flowers, knotty thorn branches’. In the

same letter Vincent quotes a well-known motto of the Goncourt

brothers: ’Japonaiserie forever’. Little did he then know

how much those words would apply to himself.

The three months that Van Gogh spent in Antwerp served as a bridge between

the Brabant countryside and Paris. In the Netherlands his subject matter

had been scenes from the hard lives of peasants and weavers. When he arrived

in the French capital in February 1886, he was immediately confronted by

the innovative ideas of the avant-garde. Theo, of course, was a familiar

figure in the art world and Vincent soon came to know a number of the youngest

group of Impressionists. They were experimenting with new techniques like

pointillism. Anyone who calls The Potato Eaters to mind, painted

as Van Gogh himself declared in the tones of a ’dirty potato’,

can imagine how challenging he must have found the colourful canvasses

of Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro and

Alfred Sisley. But the painter of drab peasant life

was to make the colourful technique of the Impressionists his own in an

astonishingly short time.

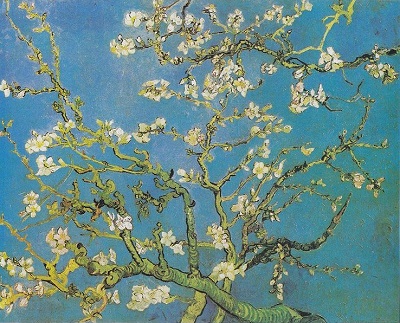

With the enthusiasm so characteristic of him Vincent studied the stylistic

innovations of the Japanese printmakers. Together with Theo he accumulated

a large collection of Japanese prints and even organised an exhibition of

them in the café Du Tambourin, a

Montmartre venue for artists that was popular with the younger generation.

In 1885 the discerning critic Théodore Duret wrote:

’Prior to the discovery of the Japanese albums no one had had the nerve

to go and sit on the riverbank and allow a bright red roof, a white wall,

a green poplar, a yellow road and blue water to contrast with each other

on a canvas.’ Duret was especially delighted by the daring way in which

nature was represented in Japanese art. For the Impressionists, who were

out to rejuvenate the art of landscape painting, the Japanese print was

an inspiring example. Their revolutionary work was characterised not only

by a striking use of colour but also by other non-European features such

as figures abruptly cut off by the margin or an emphatic contrast between

what was in the foreground and the background.

Van Gogh familiarised himself with this idiom in his own way. In the

winter of 1887 he produced three ’Japonaiseries’: copies in oil of Japanese

prints. The most ambitious of the three was based on a reproduction on a

cover of the magazine Paris Illustré. The

issue was devoted to Japan and the print depicting an ’oiran’ (a

Japanese courtesan) has been identified as by Kesai Eisen. Van Gogh carefully

traced the figure on tracing paper, enlarged it and placed it in an idyllic

water landscape with bamboo and water lilies. He derived the two frogs and

cranes from two other Japanese prints. It is no accident that the cranes

are there. Vincent was indulging in some visual word play: ’grue’,

the French word for ’crane’, also means ’tart’, thus alluding to the

courtisane.

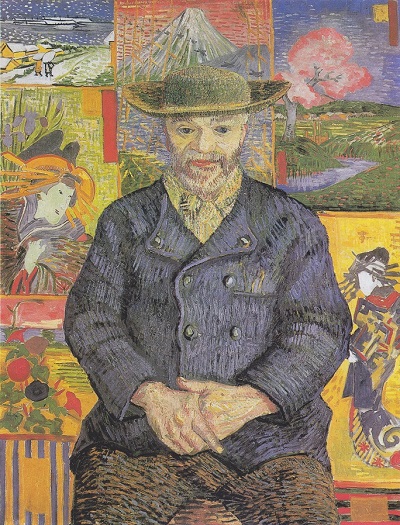

Another painting dating from the same period is the striking Portrait

of Père Tanguy. This dealer in artist’s materials

and art sympathised with the Impressionists, who found it hard to exhibit

their work. Père Tanguy allowed them the use of his

shop window and was also generous about offering artists credit. Van Gogh

was very fond of this Socialist Utopian, and Tanguy’s

kind-heartedness shines through in the painting.

As was frequently the case, Van Gogh made several versions of this portrait;

the Musée Rodin version shown here is the most elaborate.

Its relevance to this article is further enhanced by the presence in the

lower right corner of Van Gogh’s own ’Japonaiserie’ of the

oiran.

By now ’Japonism’ had come to mean more to Van Gogh than the obvious

stylistic int7uences in his own work. His image of Japan, and especially

of the way in which he believed that Japanese artists behaved towards each

other, had assumed the form of a Utopia. The disappointingly competitive

climate of the Parisian art world was no doubt also a factor. Van Gogh imagined

that instead of vying with each other Japanese artists worked together fraternally.

Someone like Père Tanguy, who was modest and

strove for a better society, fitted into that picture. This was a valid

reason for placing him against a background of Japanese prints.

Worn out and unwell after two taxing years in Paris, Van Gogh left for

Arles in the Spring of 1888. It was a wise decision, as the enthusiastic

letters he wrote after his arrival in the South of France show. To his colleague

Emile Bernard he wrote: ’Having promised to write to you I want to begin

by telling you that this countryside seems to me as beautiful as Japan for

clarity of atmosphere and gay colour effect.’ He also wrote to Theo

and his sister Wil that he felt as if he were in Japan.

A bonze in Arles